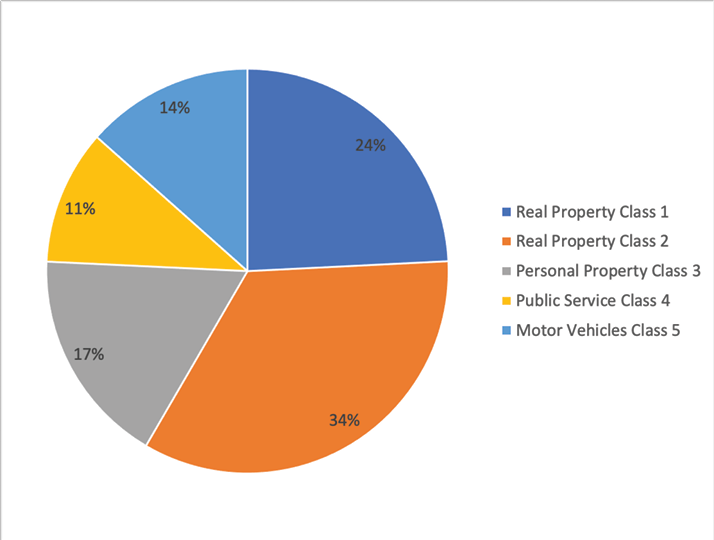

Total assessment by property class in 2018. Real Property Class 1: 24%; Real Property Class 2: 34%; Personal Property Class 3: 17%; Public Service Class 4: 11%; Motor Vehicles Class 5: 14%." width="714" height="540" />

Total assessment by property class in 2018. Real Property Class 1: 24%; Real Property Class 2: 34%; Personal Property Class 3: 17%; Public Service Class 4: 11%; Motor Vehicles Class 5: 14%." width="714" height="540" />Property tax revenues are a vital component of the budgets of Mississippi’s local governments. Property tax revenues allow these governments to provide important services, such as infrastructure, education, recreation, fire protection, and law enforcement.

In Mississippi, property tax revenues are used to fund the following:

This publication offers a brief introduction into how property taxes are determined and used in Mississippi.

Mississippi law lists five categories of property that are taxed for ad valorem purposes. Real property (land, buildings, and other permanent improvements to the land) is divided into the first two classes.

Class I real property is single-family, owner-occupied, residential property. (This is the property class to which homestead exemption is applied.) In order for a property to qualify for Class I, it must meet each of these requirements exactly. All other property that does not meet the exact definition for Class I falls into the Class II category. All agricultural, rental, and business properties and most vacant properties are considered Class II. A property can be part Class I and part Class II.

In order to assess Class I and II properties, the assessor must first determine who owns each parcel of land in the county. This is accomplished by taking inventory of the county with a mapping system that identifies ownership from deeds, wills, court decrees, and other documents. Once ownership is determined, the assessor visits each parcel to value the property and any buildings or other improvements that add value to the land. The assessor must accomplish this task by using guidelines provided by the Mississippi Department of Revenue (DOR).

Class III property is business personal property. This class includes furniture, fixtures, machinery, equipment, and inventory used by a business in its operations. The local tax assessor must list each item in every business, value the item according to DOR rules, and depreciate and revalue each item annually.

Class IV property is public utility property. Examples of public utility property include property owned by pipeline companies, electric companies, telephone companies, railroads, etc. This property is assessed on an annual basis by the DOR.

Class V property is motor vehicle property (including mobile homes). When a person purchases a motor vehicle tag in Mississippi, he or she actually pays three separate items: a registration fee, a privilege license, and an ad valorem tax. The registration fee for a new tag is $14. There is a $12.75 renewal registration fee to purchase a decal alone. Most of this fee money is sent to the state government.

The privilege license is $15 for a car and $7.20 for a truck. Primarily the county retains the proceeds from the sale of privilege licenses.

The ad valorem tax is based on the value of the motor vehicle; all values are established statewide by the DOR. Ad valorem tax dollars collected go to support local government functions where the vehicle is registered (city, county, and school district).

With only minor adjustments for homesteaded real property, the tax formula for ad valorem taxes is the same for all five classes of property:

true value × ratio = assessed value

assessed value × millage rate = taxes

True value is defined in § 27-35-50 of the Code:

“True value shall mean and include, but shall not be limited to, market value, cash value, actual cash value, property value and value for the purposes of appraisal for ad valorem taxation . In arriving at the true value of all Class I and Class II property and improvements, the appraisal shall be made according to current use, regardless of location. In arriving at the true value of any land used for agricultural purposes, the appraisal shall be made according to its use on January 1 of each year, regardless of its location; in making the appraisal, the assessor shall use soil types, productivity and other criteria . “

The point here is that true value and market value are not the same. Agricultural values, for example, can be much less than the actual market value of the property. The true value is multiplied by a ratio that is set by state law to yield the assessed value. The ratios are shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Classes of taxable property.

Single-family, owner-occupied residential property

All other real property, except real property in Class I or Class IV

Personal property, except motor vehicles and Class IV property

Public service property assessed by the state or county, except railroad and airline property

A mill is one-thousandth of one dollar, or $ .001. For example, 54.5 mills is $ .0545. Millage rates change annually. Local taxing authorities must adjust millage rates to support the operations of government. However, inflation or increased operating costs are not the only factors driving changes in millage rates at the local level. For example, a local taxing district may need additional tax revenue to pay for a bond issue. These rates are set by the governing authorities of the respective taxing districts in September for the next fiscal year beginning October 1.

State law gives general authority to the governing authorities of the respective taxing districts to administer local ad valorem tax levies. The governing authority must levy ad valorem taxes on or before September 15 at an adjourned or special meeting.

The ad valorem tax levy is expressed in mills, or a decimal fraction of a mill, and applied to the dollar value of the assessed valuation on the assessment rolls of the respective taxing district, including the assessment of motor vehicles as provided by the Motor Vehicle Ad Valorem Tax Law of 1958 (Code § 27-51-1 et seq.). In general terms, the governing authority must multiply the dollar valuation (assessed value) of the respective taxing district times the millage (levy) to produce the necessary dollars to support the budget that has been adopted.

There are limits placed on the levying of ad valorem taxes. The authority of the respective taxing districts to levy taxes is restricted by statutory limits that have been placed on the amount of any increase in receipts from taxes levied. The specific governing authority is limited to a 10 percent cap when levying ad valorem taxes. Thus, a board of supervisors or board of aldermen may not levy ad valorem taxes in any fiscal year that would render in total receipts from all levies an amount more than the receipts from that source during any one of the three immediately preceding fiscal years of more than 10 percent of such receipts.

If the 10 percent cap is exceeded, then the amount in excess over the cap is escrowed and carried over to reduce taxes by the amount of the excess in the succeeding fiscal year. Excluded from the 10 percent cap is the levy for debt service (notes, bonds, and interest), the library levy found in § 39-3-5 of the Code, and any added revenue from newly constructed property or any existing properties added to the tax rolls of the county. The 10 percent cap may be figured by fund groups individually or by the aggregate of all of the specific governing authority’s funds.

Let’s say a piece of Class II property is being valued. The assessor appraises the property at $100,000 of true value. For this example, the rate for the municipality is 35 mills, the rate for the school district is 50 mills, and the rate for the county is 40 mills. Table 2 illustrates how the tax bill would be factored and calculated.

Table 2. Sample ad valorem tax calculation.

Homeowners who are younger than 65 on January 1 of the year for which the exemption is claimed (and who are not totally disabled) are exempt from ad valorem taxes in the amount prescribed in MS Code § 27-33-7. The amount of the exemption given is determined by a sliding scale based on the assessed value of the property, which is capped at a maximum exemption of $300. See Table 3.

Half of the exemption allowed is from taxes levied for school district purposes and half is from taxes levied for the county general fund.

Table 3. Regular homestead ranges and credit amounts.

Assessed value of homestead ($ ranges)

This example shows how the taxes would be computed taking into account a regular homestead exemption for a home with a true value of $100,000. Hypothetically, the rate for the municipality is 35 mills, the rate for the school district is 50 mills, and the rate for the county is 40 mills. Table 4 illustrates how the tax bill would be factored and calculated.

Table 4. Sample regular homestead calculation.

True value–Class I

For homeowners who are older than 65 or completely disabled, the homestead exemption does not use the regular homestead exemption sliding scale. Rather, state law simply exempts the homeowner from ad valorem taxes for up to $7,500 in assessed value. In other words, a home with a true value of $75,000 or less would be exempt from all property taxes (municipal, school district, and county).

Table 5 shows how the taxes would be calculated on a home owned by someone over 65 or completely disabled. The home is located in a municipality and has a true value of $100,000. For this example, the rate for the municipality is 35 mills, the rate for the school district is 50 mills, and the rate for the county is 40 mills. The first $7,500 of assessed value is exempted. Therefore, to calculate the net tax due, rather than multiplying the millage rates by the normal $10,000 of assessed value, the millage rates are multiplied by $2,500 to reflect the $7,500 special homestead exemption.

Table 5. Sample special homestead exemption calculation.

True value–Class I

Adjusted assessed value

Units of local government do receive a partial reimbursement from the state for ad valorem tax revenue lost due to homestead exemptions. For each qualified applicant, counties and school districts receive $50 each. Municipalities are reimbursed up to the amount of the actual exemption allowed, not to exceed $200 per qualified applicant.

Starting in 2015, service-connected, total disabled American veterans who have been honorably discharged from military service and their unmarried surviving spouses are allowed an exemption from all ad valorem taxes on the assessed value of homestead property.

As discussed previously, revenue from property tax is determined by both the assessment of property and the local millage rates. Overall, property tax assessments in Mississippi have increased over the last decade. The cause for the increase in property tax assessments can be traced back to increases in property values.

Property values are influenced by several factors, including physical changes to the property or economic factors such as inflation. Millage rates have fluctuated across the state during the same time period, with local taxing districts changing millage rates as budgetary needs arise. Typically, millage rates have been set at levels that allow the local taxing districts to keep up with the cost of inflation and the increased costs of providing services.

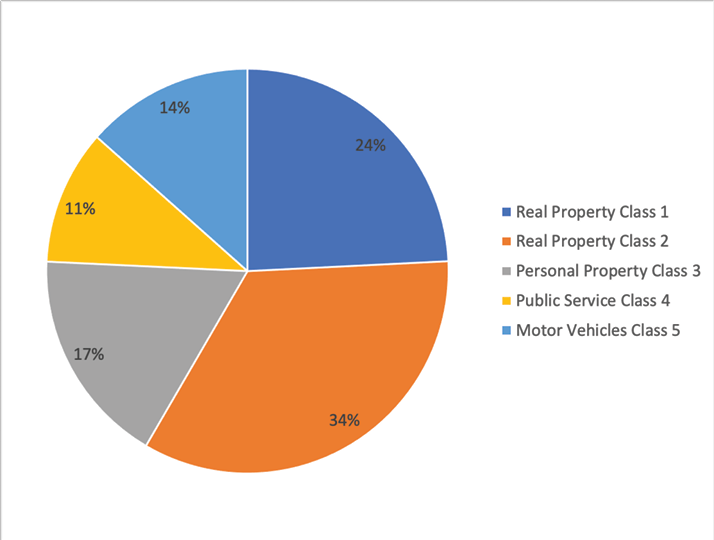

The total assessment of each property tax class contributes in varying amounts to the tax revenues of taxing entities in Mississippi (Figure 1). This is due to both the different tax rates assigned to each class and the types of properties that are included in each class. The class of property that contributes the most to total assessment is Class II real property. In 2012, Class II real property contributed 34 percent of total assessment in Mississippi.

Over the same time period, Class I real property, Class III personal property (including Class V motor vehicle), and Class IV public service contributed 26 percent, 27 percent, and 10 percent, respectively.

Total assessment by property class in 2018. Real Property Class 1: 24%; Real Property Class 2: 34%; Personal Property Class 3: 17%; Public Service Class 4: 11%; Motor Vehicles Class 5: 14%." width="714" height="540" />

Total assessment by property class in 2018. Real Property Class 1: 24%; Real Property Class 2: 34%; Personal Property Class 3: 17%; Public Service Class 4: 11%; Motor Vehicles Class 5: 14%." width="714" height="540" />

Property tax collections in Mississippi were among the lowest in the nation during 2010. Per capita, Mississippi collected $853 in fiscal year 2010. This ranked the state 39th in per capita property tax collections. See Table 6.

Table 6. State and local property tax collections per capita by state (FY2010). Source: www.thetaxfoundation.org

Collections per capita

There are several sources of revenue that county governments rely on to provide funding for the services they provide to citizens. These sources of revenue include property taxes, road and bridge privilege taxes, grants and contributions, gifts and donations, investment income, and other miscellaneous income. Of these sources, property taxes are the most important revenue generator for county governments in Mississippi, which do not receive any revenue from sales tax. For a typical county in Mississippi, more than 75 percent of revenue is derived from property tax. Therefore, the bulk of county budgetary needs are met using property tax revenue.

For Mississippi’s municipal governments, typical sources of revenues are privilege taxes, fees for services, utility system rates, franchise fees, permit fees, and ad valorem taxes. These sources of revenues are supplemented with an 18.5 percent share of the state’s sales tax collected within the corporate limits of the municipality. This infusion of revenue from sales tax collections typically reduces ad valorem taxes as a percentage of municipal revenues and, therefore, municipalities’ reliance upon ad valorem taxes as a major source of revenue in general.

In Mississippi’s county and separate school districts, property tax revenues are combined with other sources of revenue to fund basic school services and to pay for the particular district’s expenses. Sources of revenues for Mississippi school districts include property tax revenues, grants and contributions, investment earnings, 16th section sources, and other miscellaneous sources. These revenues are used to support such functions as instruction support services, noninstructional services, and interest on long-term debt. In some (but not all) instances, revenues are used to fund 16th section expenses that the county may incur.

Because municipal governments, county governments, and school districts rely on property tax revenues as a significant source of income for general operations, it is important to gauge exactly how these tax revenues are distributed. In Mississippi, county governments rely more heavily upon property tax revenues as a percentage of overall revenues than either municipalities or school districts. Yet, the percentage of overall ad valorem taxes received by local taxing districts shows school districts receiving the most, with counties receiving only slightly more than municipalities for general operations.

Property tax revenues in Mississippi play a large role in government on the county and municipal levels. While many citizens may not clearly understand how their property tax bill is derived, it is important that they are informed about where their property tax payments are going and what services these payments are funding. Property tax revenues provide the people of Mississippi with needed public services at the local level, including infrastructure, recreation, education, and police and fire protection. These services, funded through ad valorem taxes, provide Mississippi taxpayers a good return on their investment. This understanding of ad valorem taxes will lead to better engagement between citizens and local taxing districts, fostering a better overall quality of life for the state.

Publication 2833 (POD-08-23)

Revised by Jason Camp, PhD, Extension Specialist, Center for Government and Community Development.

The Mississippi State University Extension Service is working to ensure all web content is accessible to all users. If you need assistance accessing any of our content, please email the webteam or call 662-325-2262.